Exploring NotebookLM’s New Audio Overview: A Game-Changer for How We Learn

Generative AI is unlocking a new superpower: the ability to transform how we interact with information. It’s making knowledge not only more accessible but deeply personal. This isn’t just about convenience—it’s a radical reimagining of how we engage with the world of ideas. One of the fun experiments into how we restructure information is Google’s […]

Introducing VLOGGER: a leap into the future of audio-driven human video synthesis!

Introducing VLOGGER: a leap into the future of audio-driven human video synthesis! Google Research has just unveiled VLOGGER, a revolutionary framework that brings single images to life with dynamic videos created from audio inputs. Imagine generating lifelike videos of people talking, complete with head motion, gaze, lip movement, and even upper-body gestures, all from a […]

Automation has had a Ripple Effect on Gender Dynamics in the Workplace

Automation has had a Ripple Effect on Gender Dynamics in the Workplace In the 1980s, women were more likely to work in jobs at risk of automation, facing greater displacement from routine-intensive roles. Over the last four decades, women have pivoted towards higher-skill, higher-wage occupations more than their male counterparts. As a result, labor markets […]

Walmart is buying Vizio for $2.3B – What it Means for the Future of Retail, Media, and Advertising

Walmart is buying Vizio for $2.3B. The move highlights several key trends impacting the future of retail, media, and advertising: 1. Retail and Entertainment Convergence: Walmart recognizes the lines between retail and entertainment are increasingly blurring. By owning a platform that combines retail capabilities with entertainment offerings, Walmart can offer a seamless experience from entertainment […]

Are remote firms sacrificing long-term knowledge gains for short-term productivity?

Research from Natalia Emanuel, Emma Harrington, and Amanda Pallais highlights the tradeoff of being physically near your coworkers. Being close to coworkers enhances the development of skills and knowledge over the long term but may reduce output in the short run. The findings suggest working from home (WFH) offers mixed outcomes over varying time frames, […]

Navigating the Intersection of AI and Modern Romance

The landscape of love has always been complex, but the digital age has introduced a new layer of complexity. Now AI is making things even more complex. The Modern Love research, an annual study from McAfee that surveyed 7,000 people across seven countries, reveals insights into how AI and the internet are reshaping love and […]

Harnessing AI for Enhanced Profitability in Times of Diminishing Demand

Amid a shifting economic climate with diminishing fears of recession, businesses continue to grapple with economic uncertainty and emerging risks. The concept of a “soft landing” underscores the acute challenge of dwindling demand, which hampers companies’ efforts to boost revenue and, more critically, to increase profits faster than revenue. The difficulty of expanding profit margins […]

Transforming Healthcare: Navigating Technological Innovations, Policy Shifts, and Changing Patient Expectations

The playing field for hospitals is changing significantly due to various factors, including technological advancements, policy changes, patient expectations, and economic pressures. Let’s delve into some of the key areas of change. Technological Advancements: The landscape of healthcare is being reshaped by technological advancements, with telemedicine, AI, electronic health records (EHRs), and the Internet of […]

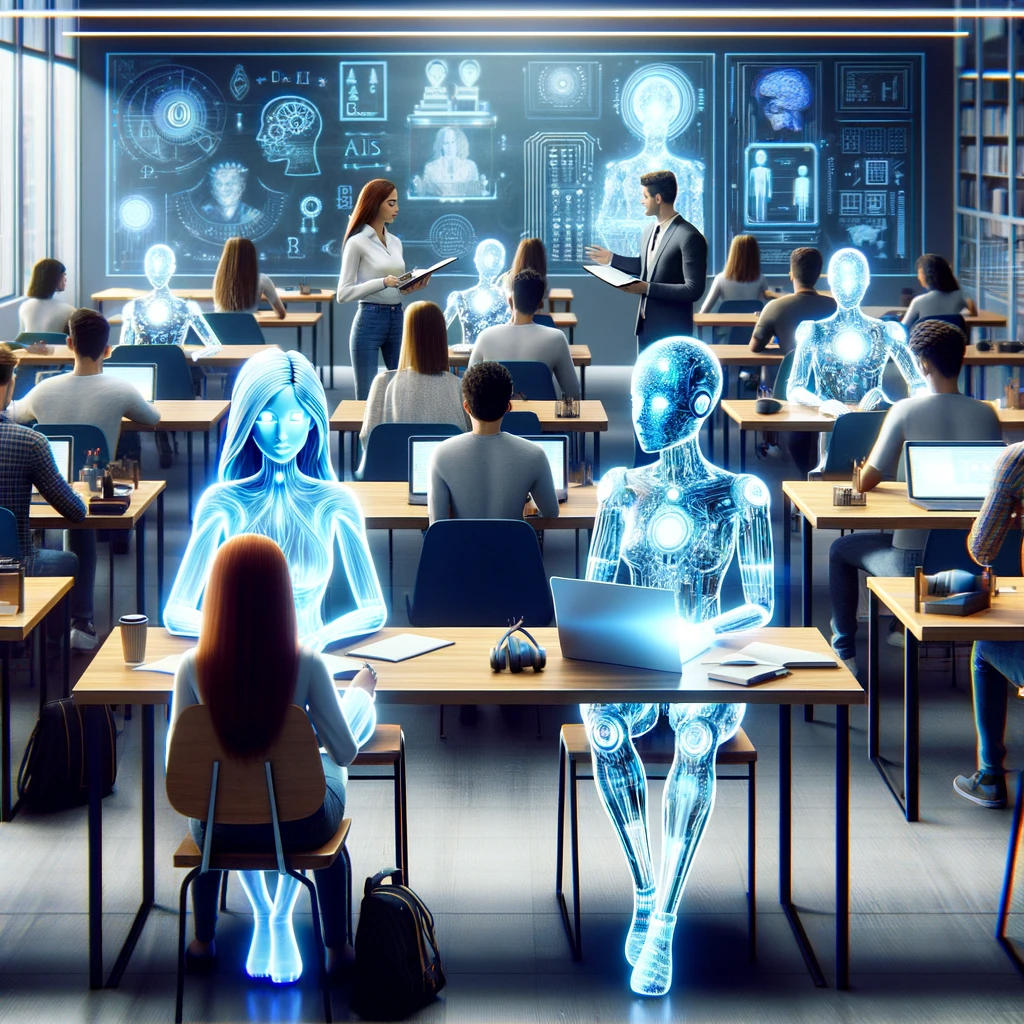

Using AI to Augment the Higher Ed Experience

Institutions are increasingly leveraging AI to rethink how they interact with prospective and current students, streamline admissions processes, and enhance student support and retention. From personalized outreach efforts that resonate with individual student preferences to sophisticated algorithms automating admissions tasks and virtual assistants providing round-the-clock support, AI is at the forefront of educational innovation. Here […]

Embracing AI in Education: A New Frontier at Ferris State University

This semester, Ferris State University in Michigan has taken a creative step into the future of education by introducing two AI-powered “freshman” students, Ann and Fry, to their academic community. Unlike typical students, Ann and Fry won’t navigate campus life as humanoid robots. Instead, they will interact with their peers and professors through computers, equipped […]